|

Battle Relic: Shrapnel

shell balls from Ypres, Belgium,

World War One, presumably British.

Introduction: From the

Hooge Crater Museum in Ypres,

Belgium, we were able to

purchase ten (10)

so-called "shrapnel balls"; lead,

marble-sized spheres, similar in

design as musket balls from earlier

times,

meant to be shot from a Shrapnel

shell "in flight".

The excellent museum, across the

road from the Commonwealth Hooge

Crater Cemetery, is located in the

heart of World War One combat

scenes.

Here the three Battles of Ypres took

place, awful weapons such as

poisonous gas (mustard gas, also

known as "Yperite") and

flamethrowers were first deployed

here, and a gigantic crater from a

mining attack on German trenches led

to the addition of “Crater” to the

name of the hamlet of Hooge, east of

Ypres proper.

|

|

Item Description: Ten

marble-sized metal balls, presumably

made out of lead, of which eight

appear to be pristine and not

ejected from a shrapnel shell by

explosion. They show wear only of

contact with other shrapnel balls.

Two balls appear to have been dug up

from the typical khaki-colored soil

of Flanders and show signs of

deformation, presumably from

striking objects after the shell in

which they were incases burst.

|

(click for

an enlargement)

|

History:

Shrapnel's invention

Shrapnel shells were anti-personnel

artillery shells which carried a

large number of individual bullets

close to the target and then ejected

them to continue along the shell's

trajectory and strike individual

targets.

The shrapnel balls relied almost

entirely on the shell's velocity for

their lethality.

Shrapnel is named after

Major-General Henry Shrapnel

(1761–1842), an English artillery

officer, whose experiments resulted

in the design and development of a

new type of artillery shell.

|

|

|

Canister & grape shot

Until lieutenant Shrapnel’s

invention in 1784, the artillery

could use "canister or grape shot"

to defend themselves from infantry

or cavalry attacks.

This type of ammunition consisted of

a tin or canvas container filled

with iron or lead balls instead of

the usual cannonball.

When fired, the container burst open

during passage through the bore or

at the muzzle, giving the effect of

an over-sized shotgun shell.

At ranges of up to 328 yards

canister shot was still highly

lethal, though at this range the

shots’ density was significantly

lower, which made it less likely to

strike a human target.

|

|

(click to enlarge)

1)

2)

2) 3)

3) 4)

4)

1)

Canister and grape shot (Fort

Defiance Visitors Center,

Clarksville, TN)

2) Grape

shot (Army Museum, Leiden, The

Netherlands)

3)

Six pounder shot shell with Borman

fuse (Fort Donelson Visitors Center,

Dover, TN)

4)

Hotchkiss shell (Fort Donelson

Visitors Center, Dover, TN) |

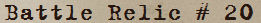

Improvement of the shrapnel shell

Shrapnel's innovation combined the

scattering effect of canister shot

with a time fuse to open the

canister and disperse the bullets it

contained.

The first designs consisted of a

hollow cast-iron ball filled with

lead balls and gun powder and fitted

with a rudimentary time fuze. After

being fired, the fuze would break

open the shell and the shrapnel

balls would carry on with the

shell's "remaining velocity".

Inside the shell a diaphragm

separated the bullets from the

bursting charge. As a buffer to

prevent lead shot to deform, a resin

was used as a packing material

between the shot.

The final shrapnel shell design,

adopted in the 1880's, used a forged

steel cone shaped case with a timer

fuze in the nose.

It also featured a tube running

through the centre to transmit the

ignition flash to a gunpowder

bursting charge in the shell base.

The use of steel allowed the shell

wall to be made much thinner and

therefore allow space for more

bullets. It also withstood the force

of the powder charge without

shattering, so that the bullets were

fired forward out of the shell case

with increased velocity, much like a

shotgun. This is the design that was

in standard use when World War I

began in 1914.

|

|

Cross section of a

shrapnel shell on display in the

Hooge Crater Museum in Ypres,

Belgium |

Size of the shrapnel balls

The size of shrapnel balls in World

War I was based on the thesis that a

projectile energy of 58 foot-pounds

force (79 Joules in the calculations

of the US Army ) to 60 foot-pounds

force (81 Joules in the calculations

of the British military) was

required to disable an enemy

soldier.

A typical World War I 3 inch (76 mm)

field gun shell at its maximum range

travelling at a velocity of 250 feet

per second, plus the additional

velocity from the shrapnel bursting

charge (about 150 feet per second),

would give individual shrapnel

bullets a velocity of 400 feet per

second and an energy of 60

foot/pounds.

This was the minimum energy of a

single half-inch lead-antimony ball

of approximately 170 grains (11

grams).

The shrapnel bullets featured in the

Battle Relic # 20 are of this weight

and are therefore of a typical field

gun shrapnel bullet size.

|

|

(click for

enlargements)

|

Shells, fuses and center tubes

littering the battlefield

The body of the shell itself was not

lethal.

Its only function was to transport

the bullets close to the target, and

it fell to the ground intact after

the bullets were expended.

A battlefield where a shrapnel

barrage had been fired was

afterwards typically littered with

intact empty shell bodies, fuzes and

central tubes.

This explains the abundance of

shells of all types and, above all,

time fuzes on display in the Hooge

Crater Museum:

|

|

(click for

enlargements)

|

Troops under a shrapnel barrage

would try to collect and bring any

intact fuzes to their own artillery,

as the time setting on the fuze

could be used to calculate the

shell's range and the location of

the firing gun.

This could lead to counter fire

missions targeting the enemy's

batteries.

All museums in the Ypres area we

have visited feature large amounts

of empty shrapnel shells.

They are literally piled up or

stacked into low walls.

|

|

(click for

enlargements)

Empty shrapnel shells stacked at the

Sanctuary Wood Museum (3 photos

on the left)

and at the Hooge Crater Museum

(right)

Empty shrapnel shells everywhere on

the grounds of the Kasteelhof Hotel

on Menin Road

(Battle Detective field office

during our stay in the Ypres area) |

Tactical deployment of shrapnel

in World War One

While shrapnel made no impression on

trenches and other earthworks, it

remained the favored weapon of the

British (at least) to support their

infantry assaults by suppressing the

enemy infantry and preventing them

from manning their trench parapets.

This was called 'neutralization' and

by the second half of 1915 had

become the primary task of artillery

supporting an attack.

Shrapnel being non-cratering was

advantageous in an assault, as

craters made the ground more

difficult to cross, although they

also doubled as safe areas and

firing positions for infantry.

Shrapnel was also useful against

counter-attacks, working parties and

any other troops in the open.

Shrapnel shells proved effective for

cutting barbed wire entanglements

only in the first stage of World War

One when the Germans used a thinner

wire.

As a result, shrapnel was only

effective in killing enemy

personnel.

The bullets also had limited

destructive effect and were stopped

by sandbags, so troops behind

protection or in bunkers were

generally safe.

Also steel helmets, both the German

Stahlhelm and the British Brodie

helmet (adapted by all Commonwealth

and armies and the US military),

could resist shrapnel bullets and

protect the wearer from head injury. |

|

(click for

enlargements)

1) 2)

2)

1)

German Stahlhelm of World War

One vintage painted over during the

Nazi era

(Camp Elsenbron Military Museum,

Belgium)

2)

Brodie Helmet of World War One of

the US Army's 82nd Infantry Division

(York Farm, Pall Mall, TN) |

|

A British ammunition

bearer wearing a Brodie helmet

(left), a Battle Detective

(right)

Hooge Crater Museum, Ypres,

Belgium |

|

CONCLUSION:

Of the ten bullets in our

possession, eight are in a pristine

condition.

These may have come from a diffused

'dud'.

We learned that the Flanders fields

are still littered with unexploded

ordnance.

The other two bullets show signs of

deformity, likely from striking

objects after being ejected from

their shell. They are also coated

with khaki colored dirt; typical of

the Ypres battlefields. |

|

EXHIBITIONS: |

|

(click for

enlargements)

Unexploded ordnance in verge of road

near Maple Copse Cemetery, Belgium |

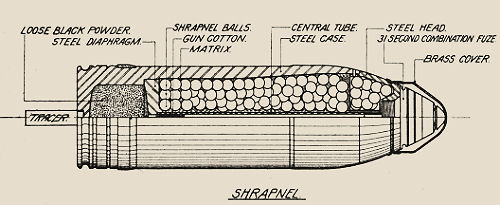

March 20th, 2014 UPDATE: On a

military show held on 02MAR2014 we

bought five (5) so-called flechettes;

little steel darts the size of one

inch nails. Flechettes can be seen

as the modern shrapnel as it is

designed to be delivered in

artillery shells and rockets in an

anti-personnel purpose. Flechettes

saw its most wide-spread use during

the Viet Nam where they were often

fired from 105millimeter howitzers

against enemy dismounted troops.

Flechettes were also fired from 12

gauge shotguns in ambush situations.

|

|

|

|

(click for

enlargements)

Flechettes are small nail sized

steel projectiles with stabilizing

fins fired in large volumes.

They weigh 0.0017oz and measure just

over an inch. The X-Ray shows impact

on a person. |

|

Back to Battlerelics

|

|

|