|

File

No.:

Title:

Still tangible evidence of

Operation Market Garden's

failure

Investigation made at: Several

locations in the Netherlands

and online databases

Period Covered:

17-26SEP1944

Date: 20AUG2025

Case

Classification:

Location of Historic

Events

Status

of Case:

Open Case

|

(click to

enlarge)

Fig.: General Browning (right

with beret), commanding officer of

1st Airborne Corps, has all the time

in the world to pose with American

Tech Corporal Matulovich of the 82nd

Airborne Division's artillery near

1st Airborne Corps Headquarters in Groesbeek. |

REASON FOR INVESTIGATION

Operation “Market Garden”,

the Allied combined arms assault

into the Netherlands with the

intention to establish a

bridgehead across the Rhine for

a ground army to advance into

the heartland of the Third

Reich, in September 1944, keeps

fascinating historians and

tacticians. The operation is one

of those great “might have been”

military stories, complete with

seemingly endless “what if

"-questions about what it was

that caused its eventual

failure.

What were the

contributing factors of

Operation “Market Garden” and

what was counteracting the

mission?

Moreover: what can

still be found as evidence of

these factors today?

This

agency mapped some of the “Still

tangible evidence of Operation

Market Garden’s failure”.

SYNOPSIS:

Categories of Errors

In general three categories of

errors that led to the failure

op Operation “Market Garden” can

be identified.

1) Errors in

the planning phase

Author

Antony Beevor, in his 2018 book

“Arnhem: the battle for the

bridges, 1944” (Penguin Books

Ltd, ISBN 9780670918676), argues

that the operation was already

flawed from the inception.

2) Errors in the execution phase

Author William Buckingham’s 2019

book “Arnhem: the complete story

of Operation Market Garden”

(Amberley Publishing, ISBN 10

1848681097 ) focusses on (mostly

British) command errors during

the operation.

Enter the

endless “what if” discussions.

“If only the weather had been

more favorable, or XXXth Corps

had kept advancing, or Nijmegen

bridge had been taken in the

first days of the operation”.

Cornelius Ryan’s 1974 book “A

Bridge Too Far” (Simon and

Schuster, ISBN 10: 024189073X)

is the best example of this

school of thinking.

3)

Errors in understanding the

opponent’s strength

Feldmarschall Helmut von Moltke,

who led the Prussian Army to

victory during the Wars of

German Unification in the

1800’s, noted that “no plan

survives contact with the

enemy.” As usual, soldiers have

a sharper way of expressing the

same thought: “The enemy has a

vote.”

This category of

errors emphasizes on

underestimating the German

strength and not foreseeing the

enemy’s response.

The best

literature on this subject can

be found in the works of Dutch

author Peter Berends in his

2003 Dutch language work “Een

andere kijk op de slag om

Arnhem, De snelle Duitse

reactie”(Uitgeverij Aspect, ISBN

90-5911-008-0) and his fellow

countryman Marcel

Zwarts’ excellent “Einsatz

Arnheim, German armoured units

and their opponents at Arnhem

1944” (MZS Publishing, ISBN

978-90-834813-0-2) in English

and published in 2024.

We will elaborate on each of

these three categories and

explain several contributing and

counteracting military factors

of the operation. When

available, we present evidence

of these factors that can still

be found today. |

|

1. Errors in the

planning phase

At

the strategic level, Operation

“Market Garden” reflected the

uncertainty that permeated

Allied planning at this stage of

the war.

The Allied

inability to secure the port of

Antwerp in Belgium caused

enormous logistical problems.

The “Red Ball Express” truck

convoys, all the way from the

artificial Mulberry harbor in

Normandy and the port of

Cherbourg to the north of

Belgium, illustrate this

challenge of logistics. The

German 15th Army managed to keep

the Scheldt estuary (and

therefore Antwerp) closed for

too long. But to make matters

worse, the Allies let this whole

army escape in a German version

of the Dunkirk retreat. A force

of ten divisions was redeployed

to the Netherlands and the

German Ruhr area, where it could

make all the difference to the

German response to Operation

“Market Garden”.

Factor

Single Main Supply Route

Operation “Market Garden” was a

very ambitious mission. It

featured many moving parts and

relied on a single highway as

the Main Supply Route. The

British XXXth Corps gave the

Lommel to Arnhem highway the

tactical name “Club Route” but

the paratroopers of the American

101st Airborne Division, who

dealt with several German

attempts to cut the Allied

corridor, dubbed it “Hell’s

Highway” for obvious reasons.

The vulnerable route north gave

the enemy a constant opportunity

to thwart the operation: cut the

road and stop the advance.

|

(click to enlarge)

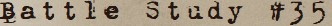

Fig.: Map showing the

Operational Plan for "Market

Garden"

with single Main

Supply Route and Phase Lines

indicating Nijmegen sould be

reached on D+2 (Tuesday

19SEP1944)

and Arnhem on

D+3. |

Factor Intelligence

The ease

and speed with which the Allies

had been able to give chase to

the Germans after the breakout

of the Normandy bridgehead had

led to the assumption that the

enemy was all but defeated.

Added to these weaknesses are

numerous poor choices made

during the planning phase. Best

known are the decision to spread

the airborne lifts over several

days, the selection of drop- and

landing zones too far from the

objectives, and the choice not

to deploy a “coup de main”

assault on the Arnhem road

bridge by inserting a raiding

party in its close proximity.

This had been proven successful

when capturing “Pegasus Bridge”

in Normandy in the night before

D-Day three months earlier.

|

Tangible Evidence of The

presence of a DZ\LZ in close

proximity to main objective

suitable for insertion of an

assault element:

1) In situ: photos taken

from DC3 on21MAY2011 of southern Rhine river

bank at Arnhem

|

(click to enlarge)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

Fig.: Embankments south of

the Rhine river road bridge at

Arnhem in 2010. After these

photos were taken (by this

agency; see

Battle Study #21) the open

fields south of the river banks

have been deepened to serve as

alluvial plains in times of high

water marks rendering this area

far less suitable for an air

assault.

Fig.: Embankments south of

the Rhine river road suitabel

for a coup de main air assault.

Note Flak-positions in open

fields of flood plain which have

to be overtaken prior to second

wave air lifts. |

The Royal Air Force's main

argument against using these

flood plains for a coup de main

was that the fly-in route for

such an air assault would be

directed from west to east

following the river. Just west

of these flood plains was a

concentration of German Anti

Aircraft Artillery (AAA)

deployed there to protect the

Arnhem bridge from incoming

aircraft. This AAA would shoot

the aircraft bringing in a coup

de main party to pieces. On the

other hand, the RAF pilot that

took the oblique photos of the

road and pontoon bridges just

days before the operation,

wasn't shot down and he flew

approximately the same route.

A truly tangible piece of

evidence for this factor is the

French 7.5 cm Flak M36 (f) gun

in front of the Deelen Museum.

It was part of those

AAA-positions and was dug up in

1996. Its crew consisted of very

young volunteers of the “Reichsarbeitsdienst”

(German State Labour Service).

They were assisted by POW’s from

Belarus who did the heavy work.

On day one of the Battle of

Arnhem, all commanding officers

of the artillery battery had

become casualties, and the canon

became unusable. One of the

recuperators (shock absorbers)

failed. Also, the crew’s

ammunition supply was down to

just smoke grenades and

armor-piercing shells which were

virtually unsuitable for either

the overcoming aircraft or the

advancing airborne troops

advancing from Oosterbeek to the

Rhine road bridge.

The crew,

therefore, decided to abandon

their artillery piece. A "Sprengkommando"

(German demolition squad)

subsequently disabled it. This

is still clearly visible: both

the demolished recuperator and

the holes in the breech block

rendered the gun inoperable.

The museum in Deelen has

located, salvaged, and restored

this canon after it had been

buried in the flood plains of

the Rhine River for 52 years.

Remarkably, after thorough

research, they even managed to

track down the original crew.

|

(click to enlarge)

_small.jpg)

Fig.: Captured French 7.5 cm

gun belonging to "gemischte

Flak-Abteilung 594".

First

picture photographed

on 25AUG2014, second on 17FEB2024 and third on

20AUG2025.

Note that in 2013 the

museum had painted the gun in

the German "Gelb-Grün-Rot"

camouflage scheme with "Emil" on

it as this was the name of this

particular gun in "1. Batterie".

When we found it in 2024 it

was painted in the early war

dark grey Wehrmacht color and in

2025 it was in "Gelb-Grün-Rot"

again with just the letter "E"

on the barrel as it was in 1944.

Fig.: Low-level oblique photo of

the Arnhem bridge

taken by

541 Squadron on 6SEP1944.

On

12SEP1944 RAF pilots also took

the photo shown below with the

pontoon bridge on it

and

again could do this unopposed by

AAA-fire. |

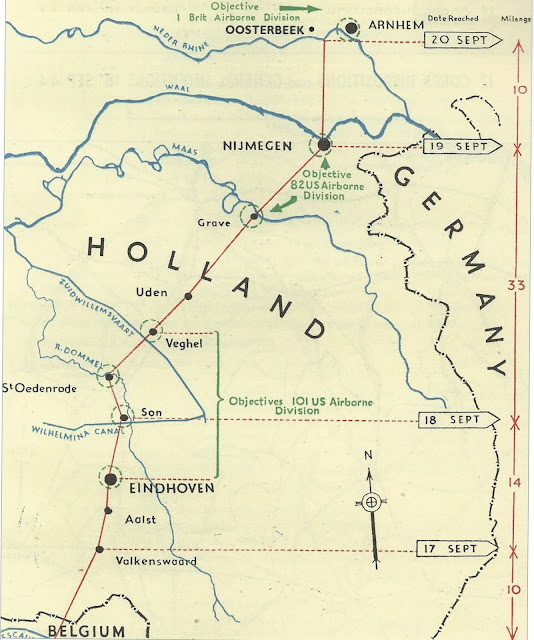

2) Diagrams comparisons of

LZ at Pegasus Bridge and

imaginary of a fictitious coup-de-main landing

at Arnhem Bridge. |

(click to enlarge)

Fig.: Left: British Horsa

gliders landed near "Pegasus

Bridge" near Benouville in

Normany in the night of

5-6JUN1944

Right:

FABRICATED

image of what it would look like

if Horsa gliders had landed

south of Arnhem bridge on

17SEP1944 |

|

It is often said that

Operation “Market Garden” was

essentially an intelligence

failure.

British intelligence

officer Major Brian Urquhart,

not related to Major-General

Urquhart the commander of 1st

Airborne Division, warned about

the presence of the 2nd SS

Panzer Corps, but was ignored as

can be read in

Case File #19. It is however

a fact that the greater Arnhem

area was not infested with

German armor when the air

assault started.

|

Tangible Evidence of

Limited presence of German armor

in the Arnhem area on 17SEP1944:

1) From the NIOD archive in

Amsterdam: Messages from the

Dutch Underground sent shortly

before the start of Operation

“Market Garden” only indicate

the presence of the 9th

“SS-Panzer-Division

Hohenstaufen” in the area north

of Arnhem.

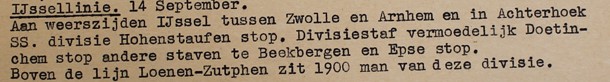

Fig.: Typed message either sent

from occupied Netherlands to

Londen via microfilm or in

encrypted Morse radio messages

informing: "IJssel

Line.14 September. Both

sides of IJssel river between

Zutphen and Arnhem and in

Achterhoek region SS. division

Hohenstaufen stop. Division

staff presumably in Doetinchem

stop other staff elements at

Beekbergen and Epse stop. Above

line Loenen-Zutphen are 1900 men

of this divison".

On this note,

it is a mystery to this agency

that the presence of 9th and

10th SS Panzer division came as

a surprise to the men of 1st

British Airborne division when

reference is made to at least

one panzer division in that Area

of Responsibility in the

Intelligence Summary of the 82nd

Airborne Division dated

11SEP1944. Was this intelligence

not available to the British and

if so; why not?

|

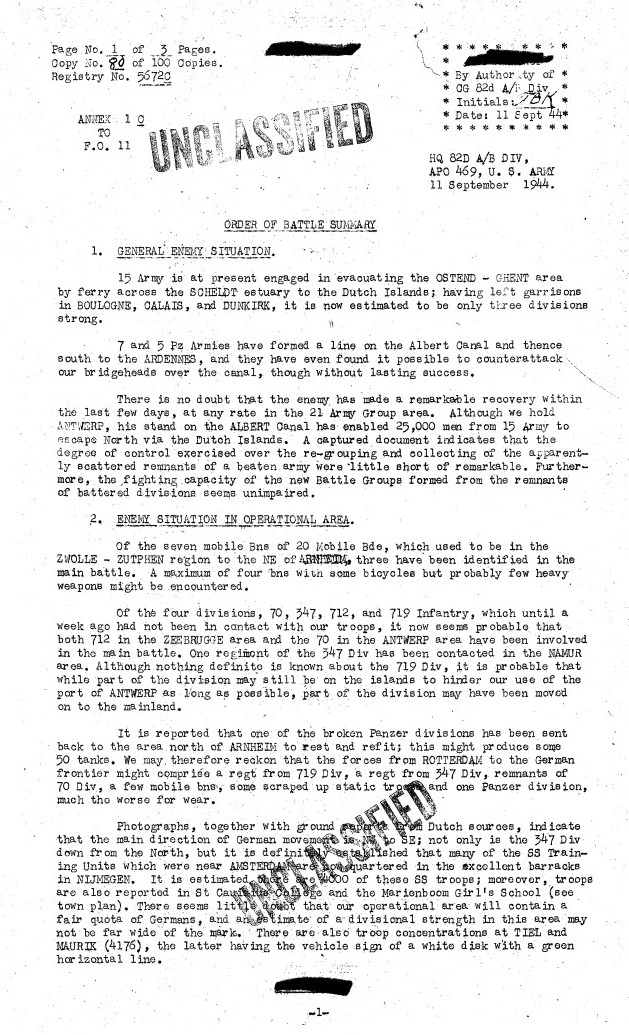

(click to enlarge)

Fig.: Annex 1C to

Field Order 11 of the 82nd

Airborne Division describing in

an Order of Battle Summary the

Enemy Situation in the

Operational Area:

"It

is reported that one of the

broken Panzer divisions has been

sent back to the area north of

ARNHEIM to rest and refit ; this

might produce some 50 tanks. |

|

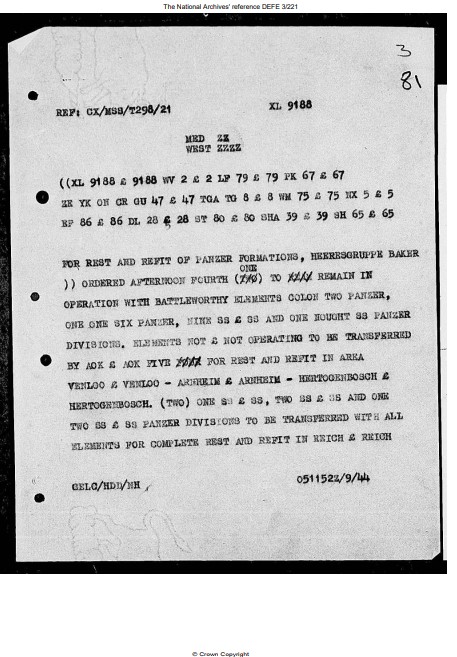

2) From the

National Archives in the

UK:ULTRA Intercepts relating to

ENIGMA messages about deployment

of 2nd SS Panzer Corps in Arnhem

area |

(click to enlarge)

Fig.: Intercepted and

decyphered message of 05SEP1944

ordering 9th and 10th SS Panzer

Division to rest and refit in

Arnhem area. |

It was the German ability to

reinforce the units already in

the area that formed the

greatest threat.

The overall

plan was too fragile to

withstand the first opposition

met once the starting phase line

was crossed and airborne troops

started landing. It lacked the

flexibility to deal with the

inevitable setbacks such as the

ambush at the Dutch frontier and

the destruction of the

Wilhelmina Canal bridge at Son

both on the first day of the

operation. And, worse, to deal

with an active enemy who did not

react as Allied planners had

assumed.

|

Tangible Evidence of

Unpredicted enemy delaying

Advance of “Garden”:

1) In situ: German ambush

positions along N69 south of

Valkenswaard

|

(click to enlarge)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

Fig.: Indentations in forest floor

along MSR (now Highway N69)

where German soldiers operating

anti-tank equipment laid in wait

for the lead elements of British

XXXth Corps on 17SEP1944.

.jpg)

Fig.: Lidar image of the

same forest floor today. |

|

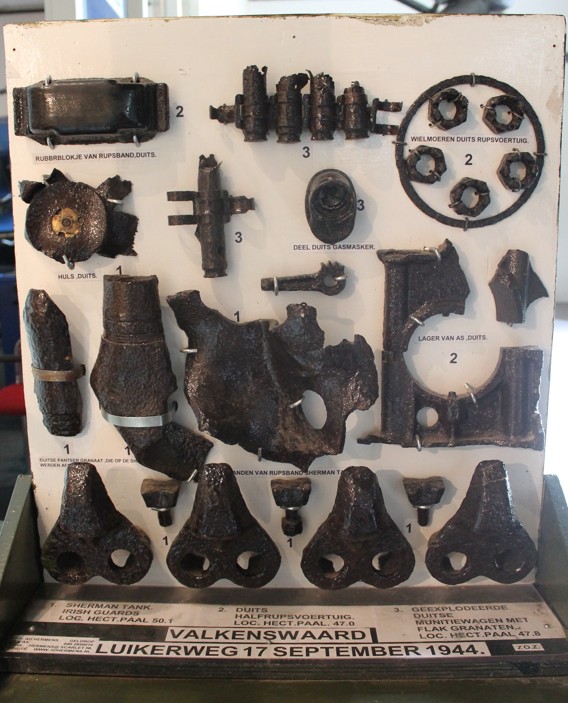

2) In the

Wings of Liberation Museum in

Best: British vehicle parts

found along N69 south of

Valkenswaard. |

(click to enlarge)

Fig.: Battlefield relics

donated to the

Wings of Liberation Museum in

Best, the Netherlands

marked where they were found

(proximity to hectometer

distance signposts). |

2. Errors in the

execution phase

Most

likely the largest of errors in

the prosecution of the operation

was the delayed capture of the

Waal river road bridge at

Nijmegen. The main effort of the

airborne troops was to capture

all bridges en route to Arnhem

with “thunderclap surprise”,

which absolutely meant top

priority immediately after

landing. Unfortunately the task

and prioritization of capturing

Nijmegen bridge was given and

discussed in verbal order; not

in writing.

It should be

noted here that the US 82nd

Airborne Division had received

an incorrect intelligence report

about large numbers of German

tanks hidden in the Reichswald

forest on the eastern flank of

the Division’s drop- and landing

zones. This was also the area

where First Allied Airborne

Corps commander General

Frederick “Boy” Browning planned

to establish his headquarters.

These factors resulted in

prioritizing the capture of the

Groesbeek Heights at the expense

of the immediate advance in

force into Nijmegen.

|

Tangible Evidence of

Questionable command decision:

Moving entire HQ 1st

Airborne Corps to field at

expensive of transport

capabilities that could

otherwise have been deployed for

war fighting elements

1) In close proximity to the

LZ of 1 Airborne Corps HQ: monument with Horsa

Glider parts in Groesbeek

|

(click to enlarge)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

Fig.: Monument othe corner

of 17 Septembers Straat

and Parachutisten Straat

in Groesbeek honoring the

landing of 1st Airborne Corps

Headquarters.

Note "V"-shaped

element made from landing gear

wheel suspension of one of the

Horsa gliders bringing in

General Browning's staff.

Also note bullet holes in the

tubing.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Fig.: Monument on

Koning Juliana Weg in Groesbeek

honoring General Browning's

Headquarters. |

Although XXXth Corps can be

accused of lacking a sense of

urgency in their advance on

18SEP1944 (D-Day+1), the bridge

they needed to cross (Nijmegen)

was still in enemy hands.

Their participation in capturing

that bridge had not been

pre-planned, and XXXth Corps had

to spend much of its offensive

power in support of the 101st

and 82nd Airborne Divisions.

|

Factor Weather

The original plan was that the

remainder of 1st Airborne

Division would land in the

second airborne lift no later

than 1000 in the morning of

18SEP1944 but cloudy conditions

prevented air assets from taking

off before midday. It was not

until between 1500 and 1600 that

they arrived over the drop- and

landing zones.

After

19SEP1944, 7 of the next 8 days

had poor weather and all air

operations were cancelled on 22

and 24SEP1944. This left the

101st and 82nd Airborne

Divisions without their

artillery for days and the

latter division without its

glider infantry regiment for 4

days. The British 1st Airborne

division had to do without its

4th Brigade until five days into

the operation.

|

Factor Armored Corps

Doctrine (strictly daylight

operations with infantry

support)

Armored

assaults in darkness are

difficult and the lead elements

of the Guards Armored Division

tanks had little infantry

support.

Above all, they were

restricted to that one elevated

highway. A continued charge past

Nijmegen might have pushed the

German defenders off balance;

but a swift and bloody repulse

appears the most likely end

state.

|

Factor Close Air Support

The contribution of the Allied

air component was at times

perfect. For all the undoubted

bravery of the transport crews,

there were problems in supplying

the trapped division at Arnhem,

and delivering tactical air

support. All too often,

especially at Arnhem, Allied

tactical airstrikes were

unavailable. Sometimes it was

the weather, though more often

it was the inability to run both

types of mission simultaneously

in such a small area. When the

Typhoons could get in, however,

they were devastating. More

close air support might have

compensated the slow advance of

XXXth Corps.

|

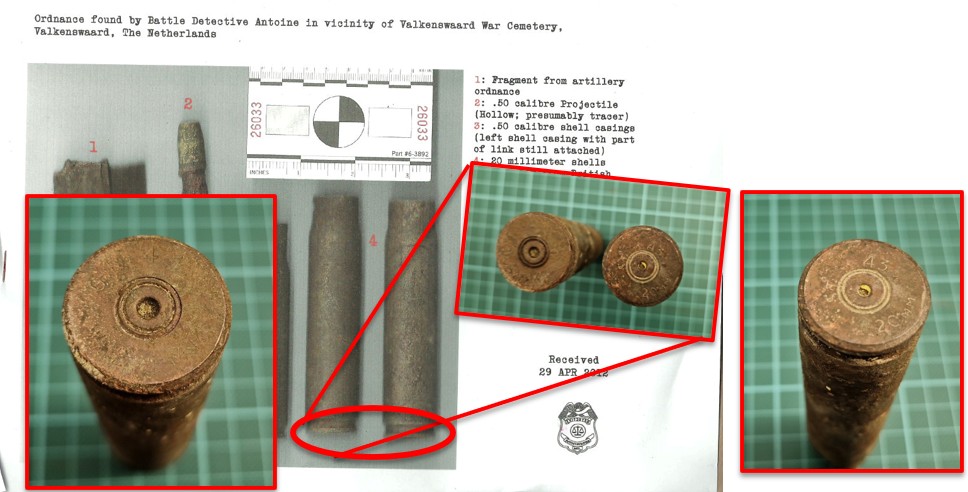

Tangible Evidence of The

deployment of Close Air Support:

Found in situ and in possession of this agency:

Two 20mm Hispano cannon casings

presumably from strafing runs by

Hawker Typhoons, found near

Commonwealth cemetery along N69

south of Valkenswaard by Battle

Detective Antoine in close

proximity to the German

anti-tank ambush location.

|

(click to enlarge)

Fig.: 20 millimeter shell

casings found by Battle

Detective Antoine close to the

N69 South of Valkenswaard;

presumed to be from 20 mm

Hispano autocannons in British

Hawker Typhoons

providing

close air support on 17SEP1944. |

Factor Command and

Control

Commanding

Officer of the 1st British

Airborne Division, Major-

General Roy E. Urquhart, was

trapped in a townhouse on the

line of contact with the enemy

in Arnhem. He spent hours out of

touch with his own headquarters.

For the whole division, an

already complicated situation

was made far worse because of

this.

|

Tangible Evidence of

Command and Control Error

In situ: house on Zwarteweg 14 in Arnhem

where Major- General Roy E.

Urquhart was trapped in the

attic with sign “Urqhuart House” |

(click to enlarge)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Fig.: Townhouse on No. 14

Zwarteweg in Arnhem where

Major-General Roy E. Urquhart

and two other British

Airborne officers had been

hiding for hours on

17-18SEP1944.

Note sign

"Urquhart House". |

General Browning, supposedly

commanding all of the airborne

troops from his headquarters in

the woods near Groesbeek, proved

inept and out of reach.

Montgomery failed to control the

situation at all, while Horrocks

was probably too ill to be in

command.

Exemplary is

also the touristic battlefield

tour made by general Ridgway who

started his journey with General

Brereton. Both generals were stuck in Eindhoven

during the bombing raid on the

city 19SEP1944. They had to

abondon their staff car and

Brereton stayed in Eindhoven,

while Ridgway proceeded north

along Hell's Higway only to be a

nuisance for General Gavin in his HQ just when

the urgency of taking Nijmegen

Bridge became apparent.

|

(click to enlarge)

Fig.: Now&Then comparisson

of the corner of August Snieders

Laan in Eindhoven where General

Brereton's staff car was

abandoned and from where General

Ridgeway arranged for his own

transportation to the 82nd

Airborne Division's Area of

Responsibility.

|

On the opponent’s side we’ve

seen in “Kussin Junction” the

choice of Feldkommandant

Generalmajor der Infanterie

Friedrich Kussin to visit the

front-line troops of

SS-Haupsturmführer Josef Krafft

which turned out to be a fatal

leadership decision.

|

.jpg) |

Nevertheless the ad hoc battle

command of Feldmarschal Model,

Generalkommissar für das

Sicherheitswesen Rauter and

SS-Oberst-Gruppenführer Bittrich

took over operations, and

concurred.

|

Factor Signals

Communication

The

radios flown in to Arnhem were

mostly not up to the task and

failed repeatedly.

|

Factor

Wet Gap Crossing Capabilities

The problem of boats, bridging

materiel and river crossing

capabilities is often mentioned.

A look at the map shows that

this was likely to be a key

element of the operation. Surely

there were not enough boats and

amphibious vehicles, but these

were too slow and unsuitable for

a wet gap crossing under fire

anyway. This wasn’t an airborne

infantry task either.

|

Commander’s Intent:

Cross the Rhine from the current

position.

Many

publications state that the

intention of Operation "Market

Garden" was to by-pass the

Siegfried Line; known in German

as the Westwall (=

western bulwark). This was a

German defensive line built

starting in 1936, opposite the

French Maginot Line. It

stretched Kleve on the border

with the Netherlands, along the

western border of Nazi Germany,

to the town of Weil am Rhein on

the border with Switzerland. The

line featured more than 18,000

bunkers, tunnels and tank traps.

This agency is of the

opinion that the Operation’s

main effort was to cross the

Rhine starting from the current

position of the British Second

Army.

The intent of the

commander ordering the operation

(Field Marshal Bernard L.

Montgomery) is described in the

document "Operation

SIXTEEN (scrathed) "MARKET",

Outline Plan, INFORMATION" of

First Allied Airborne Army,

11SEP1944:

"2.

Own Troops

Guards

Armoured Division is across the

canal in the area HASSELT –

HECHTEL – BOURG LEOPOLD.

50

Division an s 11 Armoured

Division are fighting for

bridgeheads between Guards

Armoured Division and ANTWERP.

15 Division is reaching ANTWERP

today.

It is

the intention of the

Commander-in-Chief 21 Army Group

to advance NORTH across the

MAAS, WAAL and NEDER RIJN, form

a strong bridgehead NORTH of

ARNHEM and continue his

operation NORTH into HOLLAND and

EAST against the REICH. The main

axis of the advance is EINDHOVEN

– GRAVE – NIJMEGEN – ARNHEM.

INTENTION

3.

Airborne Corps will capture and

hold crossings over the canals

and rivers on Second Army’s main

axis of advance.”

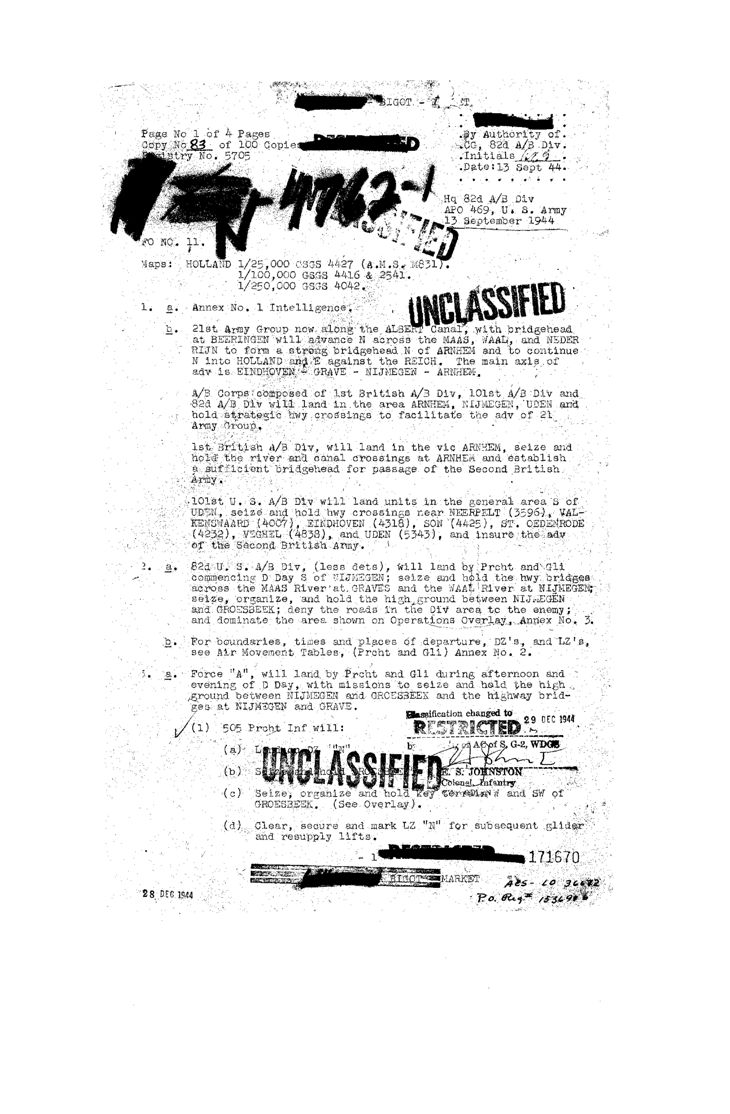

This intention is in turn

repeated in the detailed orders

of the divisions comprising 1st

Airborne Corps; in this example

in Field Order No. 11 of the

82nd Airborne Division,

13SEP1944: |

(click to enlarge)

|

“b. 21st Army Group now

along the ALBERT Canal, with

bridgehead at BEERINGEN will

advance N across the MAAS, WAAL,

and NEDER RIJN to form a strong

bridgehead N of ARNHEM and to

continue N into HOLLAND and E

against the REICH. The main axis

of adv is EINDHOVEN – GRAVE –

NIJMEGEN – ARNHEM.

A/B Corps

composed of 1st British A/B Div,

101st A/B Div and 82 A/B Div

will land in the area ARNHEM,

NIJMEGEN, UDEN and hold

strategic hwy crossings to

facilitate the adv of 21 Army

Group.”

|

No mention is made of the

Siegfried Line and the aim of

outflanking this fortification.

The intention starts with the

description of Second Army’s

position in an East to West

horizontal frontline more or

less parallel to the

Belgian-Dutch frontier. It is

therefor likely that the

intention of advancing north

onto Holland originates from a

desire to cross the main

Western-European rivers where

the opposition is expected to be

less lethal than in the Reich

itself.

A pivotal maneuver of

the Second Army in Eastern

direction and straight across

the Rhine river through the

Eiffel Forest would likely prove

deadly for the attackers.

One a side note, the intention

fails to mention how the

commander foresees the crossing

of the last river after forming

"a strong bridgehead N of

ARNHEM and to continue N into

HOLLAND and E against the REICH";

that is the river IJssel.

It

can be ruled out that the axis

of advance as planned, was

designed to by-pass the

Siegfried Line as it is not

mentioned in the order but stems

from the 2nd Army’s pre-mission

position at the intended start

line.

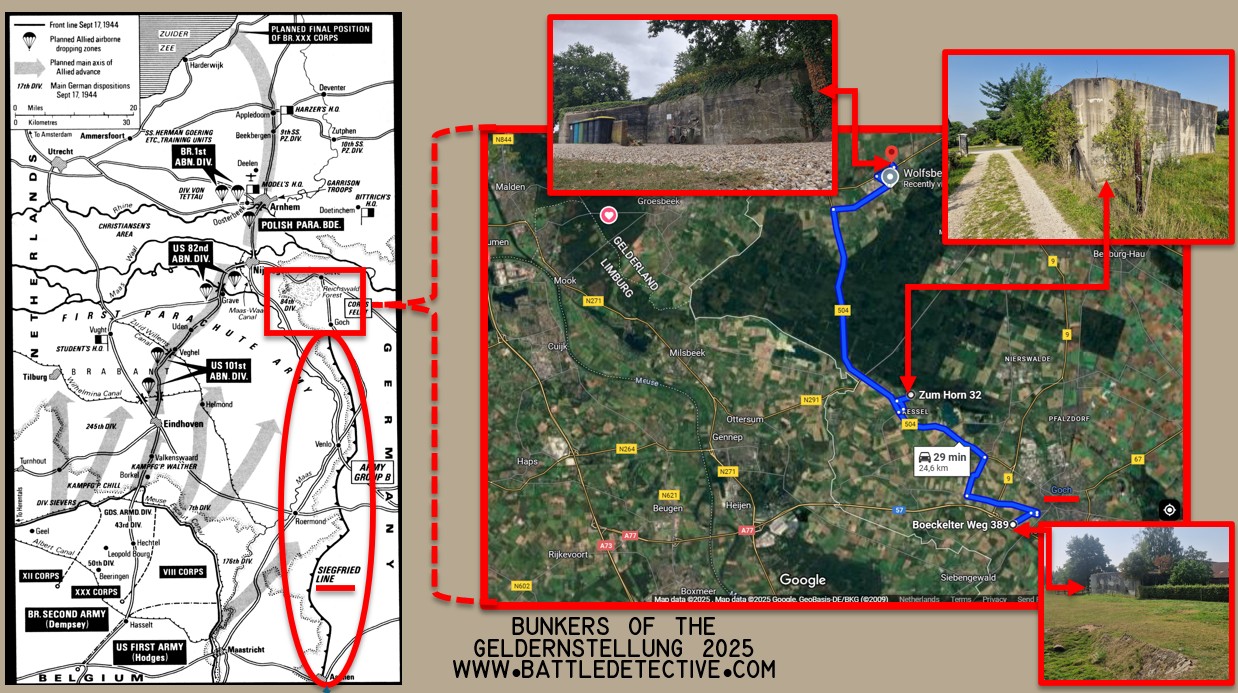

Moreover it is the

opinion of this agency that the

presence of the Siegfried Line

should not have been a factor

anyway in deciding to advance

into Holland and subsequently

East into Germany. The Siegfried

Line and its Northern section,

the "Geldernstellung" were

obsolete by the Fall of 1944 and

as a defensive feature would not

have stopped the advance of the

Second Army. Today several

concrete pillboxes and casemates

of the Geldernstellung can be

found east of the Area of

Operations of "Market Garden":

|

(click to enlarge)

|

Tangible Evidence of The

Challenges of advancing on a

single MSR with multiple wet gap

crossings:

The route

of advance north of the ground

troops featured numerous

waterways to cross. Two wet gaps

along Hell's Highway turned out

to be delaying obstacles: the

canal bridge at Son destroyed by

the enemy on D-Day of the

operation and the river bridge

at Nijmegen that had yet to be

captured when the ground troops

reached the city on D+3. And

then of course the river bridge

at Arnhem of which the northern

ramp was captured by airborne

elements on D-Day to D+3 but

never reached by the grounds

elements of XXXth Corps.

These waterways still exist and

haven't changed significantly

since "Market Garden".

1) in

situ: photo

series of RNLA constructing

Bailey Bridge across Wilhelmina

Canal at Son on17SEP2014.

|

(click for enlargements)

_small.jpg) _small.jpg) _small.jpg) _small.jpg)

_small.jpg) _small.jpg) _small.jpg) _small.jpg) |

|

2) in situ: photo series of Waal

River Crossing reenactment 19-20-21SEP2024. |

(click for enlargements)

_small.jpeg)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

|

3) In situ: (Neder) Rhine river

at Arnhem. A river that runs

from Switzerland to the North

Sea. During the withdrawal in

the night of 25-26SEP1944, many

British paratroopers swam away

from the Oosterbeek perimeter to

the southern banks. Although we did swim

the river Rhine on 19JUL2024

(from the Swiss bank at

Rheinauerweg 1 in 8447

Dachsen, to the German side and

back, there where the river is

wide but with strong currents),

swinging the same river at

Arnhem and Oosterbeek is not

only dangerous as signs by the

river tell, it is also illegal.

If caught swimming in the

river's fairway one can be fined

EUR 170,- (rate of 2025) by the

Dutch Department of Waterways

and Public Works ("Rijkswaterstaat").

And this is not without a

reason. Although the river is

narrower and the current seems

slower than the river Waal at

Nijmegen, the Rhine can be

treacherous and has claimed the

lives of swimmers in the past.

Also today it is easy to tell

that the loss of the existing

river bridges would cause

challenges for the attackers as

a Bailey bridge of the size as

the one in Son would not be

enough to cross this obstacle. |

(click for enlargements)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

Fig.: Rhine river bank at Arnhem

with warning sign and poster:

Swimming the Rhine here is

dangerous and illegal.

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

Fig.: The river Rhine at Dachsen

in Switzerland which we crossed

by swimming in 2024.

Fig.: left to right: first

Bailey Bridge named "Campbell

Bridge" at the site of the

pontoon bridge in 1945,

that

same year a double Bailey bridge

named "Foulkes and Simonds" was

constructed east of the river

road bridge,

in 1946 a more

permanent Bailey bridge was

finished until the original

bridge was reconstructed in

1950.

|

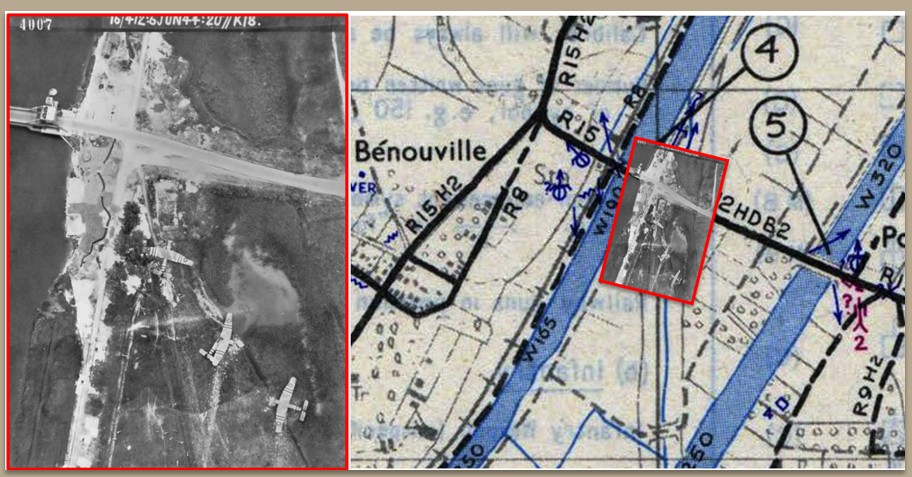

4) In situ: The pontoon bridge

across the river Rhine at

Arnhem, which had become

obsolete with the completion of

the road bridge in 1935, was an

objective of the paratroopers

who were also tasked with taking

the latter river crossing. On

17SEP1944 the paratroopers of

LT-COL John Frost found the

center section of the bridge on

the southern river bank and left

the bridge behind.

In a

"What-If-"scenario one can

discuss what tactical advantages

the intact pontoon bridge would

have provided the British

airborne soldiers. They might

have been able to put troops on

the southern bank and attack the

road bridge from both sides. |

(click for enlargements)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

Fig.: Pontoon "GWA 14"

for Municipal Works Arnhem No.

14,

which was found in

derelict state in 2007 was

restored

and sits on the

spot where the south end of the

pontoon bridge was.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Fig.: Left: On an oblique aireal

photo taken on 12SEP1944 the

center section of the pontoon

bridge

can be seen dragged

mid-river and away from bridge.

Right: On a vertical

aireal photo taken during the

battle (not smoke above the

town),

the center section

can be seen neatly "parked" on

the southern bank. |

3. Error in

Understanding of Opponent’s

strength

During the

entire operation, the German

defense was highly competent and

capable of frustrating the

Allied plans. German units

remained tactically sharp. The

immediate response to the

initial Allied airborne assault

showed a high degree of

initiative on local levels. The

troops were well led and, even

against elite paratroops, they

held their own. This bought the

Germans precious time and

allowed for defensive positions

to consolidate, particularly in

Arnhem.

The German

situational understanding,

planning, organization, and

decision-making were exemplary

at the operational level.

Especially Feldmarschall Walter

Model of Army Group B and

SS-Obergruppenführer Wilhelm

Bittrich commanding the 2nd SS

Panzer Corps, quickly understood

the situation and reacted

accordingly. Deploying the

troops they had, Kampfgruppen

were formed and counter-attacks

were already threatening the

Allied offensive within 24

hours. This performance makes

that of Horrocks and Browning

look uninspiring.

|

Factor Operational

Security

On

15SEP1944 the alleged betrayal

by Dutch double agent Christiaan

“King Kong” Lindemans of an

imminent combined arms assault

into southern Holland took

place. Tasked by Allied command

to cross the lines into occupied

Holland to inform resistance

groups of the imminent

operation, King Kong first went

to the Generaloberst Kurt

Student, in charge of the German

defense of occupied Holland.

There he told of a planned

armored assault in the direction

of Eindhoven. Student had King

Kong transferred to the Abwehr

(Counterintelligence)

headquarters in Driebergen to be

debriefed indepth. King Kongs

double cross betrayal can at

least be viewed as another

confirmation of what the Germans

were already expecting:

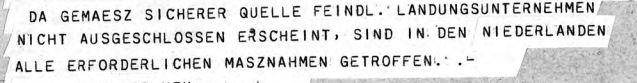

|

(click to enlarge)

Fig.: From the OB West

Tagesmeldebuch 11SEP1944

"Reliable source says invasion

is imminent and all precautions

are taken in Holland" |

Tangible Evidence for the

Betrayal of the operation by

Double Agent Christiaan “King

Kong” Lindemans:

1) In situ:

Photos of Lindemans’ grave in

Crooswijk.

|

(click to enlarge)

.jpg)

.jpg)

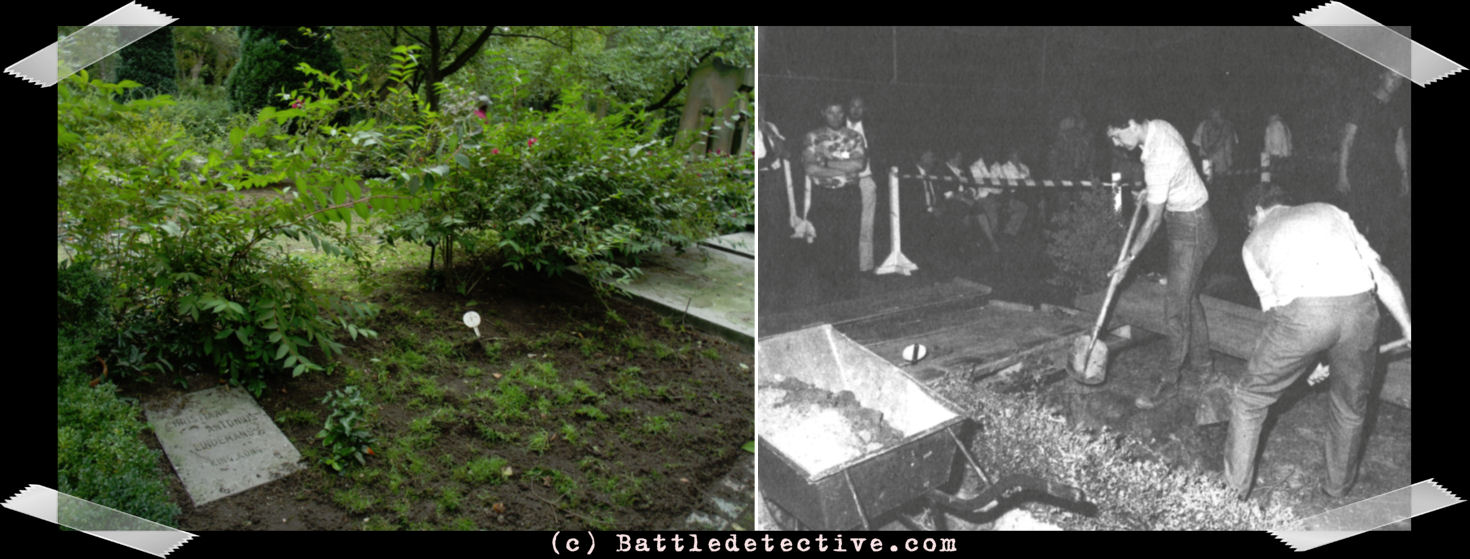

Fig.: Christiaan "King Kong"

Lindemans' grave today and

exhumation of his remains on

17JUN1986.

After examination

it was determined that the

exhumed remains could indeed be

identified as those of

Lindemans, that anatomically no

cause of death could be

identified from the skeleton,

and that there were insufficient

arguments to demonstrate arsenic

poisoning. Everything seemed to

indicate that Lindemans had

indeed committed suicide. |

|

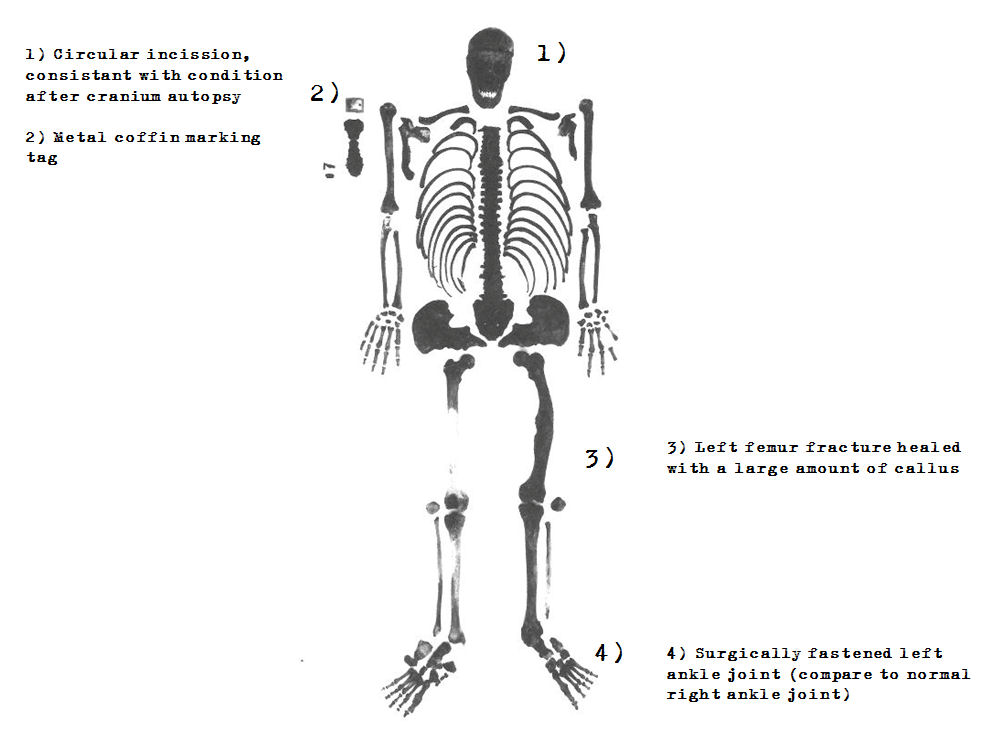

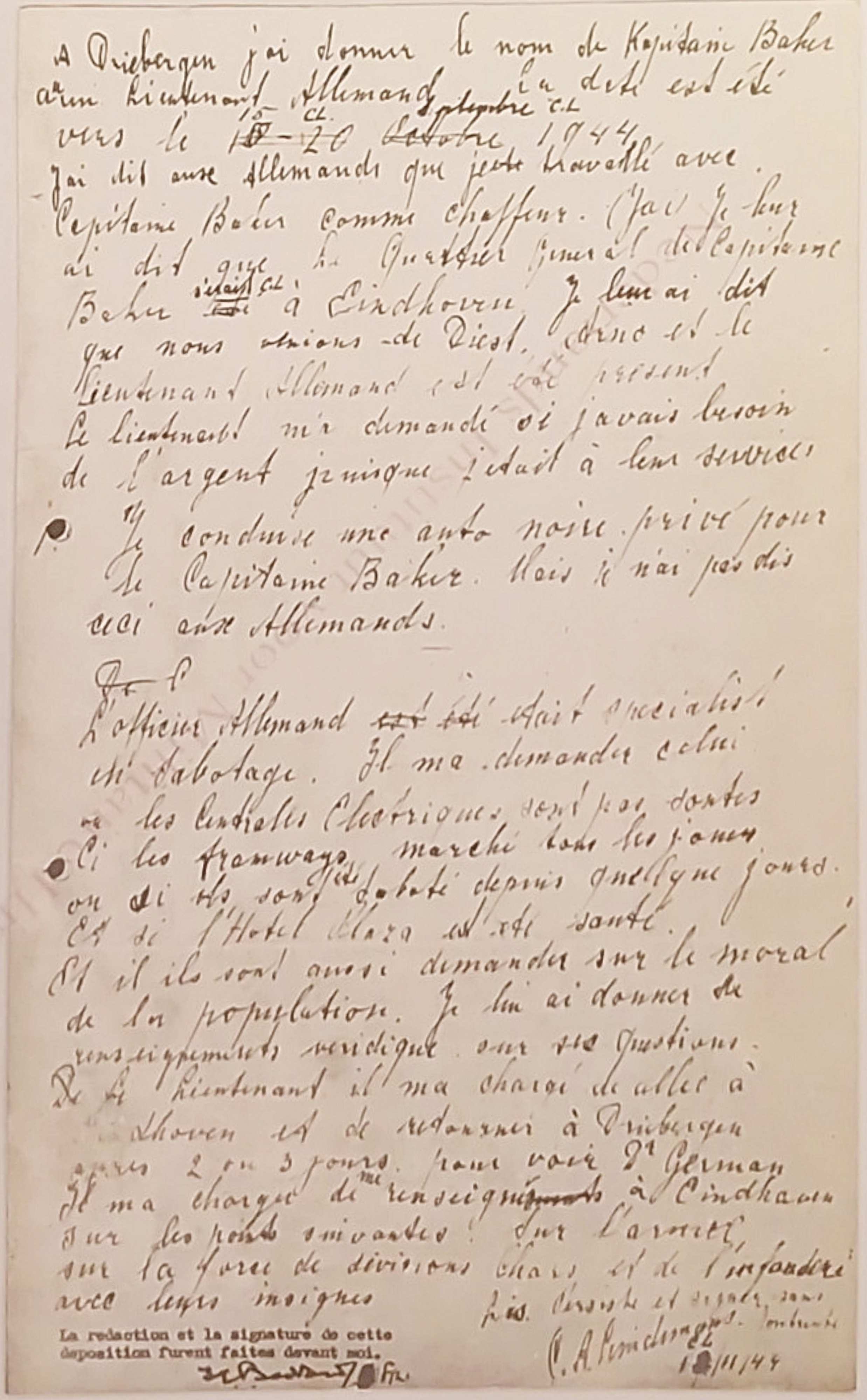

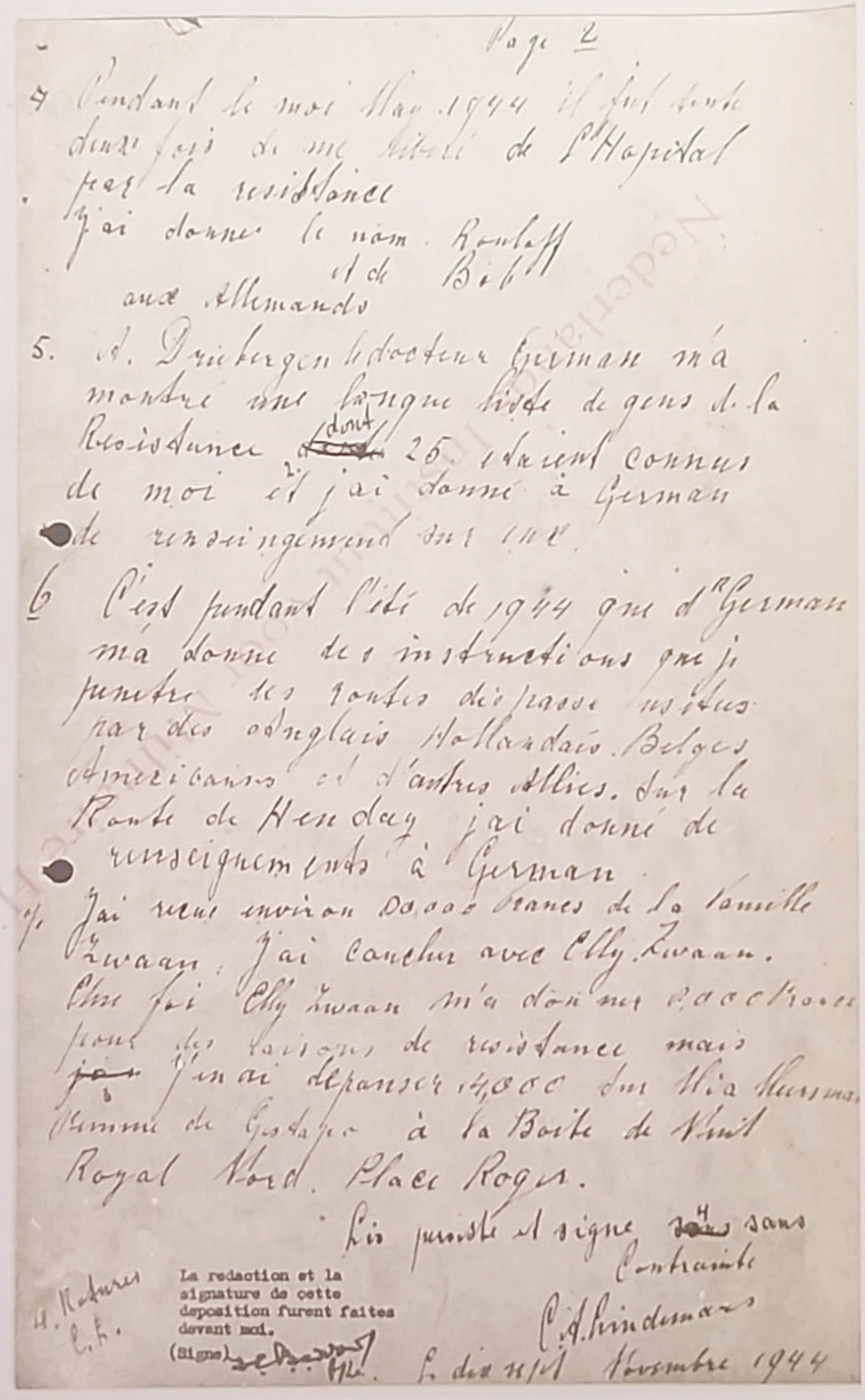

2) In the NIMH

Archives in The Hague: King

Kong’s handwritten statement in

French of NOV1944. |

(click to enlarge)

Fig.: Two pages in

Christiaan "King Kong"

Lindemans' own handwriting in

which he only admits to Canadian

Field Security that in

Driebergen he betrayed his

handler Captain Baker and the

resistance network he was a

member of; nothing about

divulging military intelligence. |

|

3) In

Boerreé’s book: German report

with intelligence from a

“V-Mann” which can only be King

Kong. |

(click to enlarge)

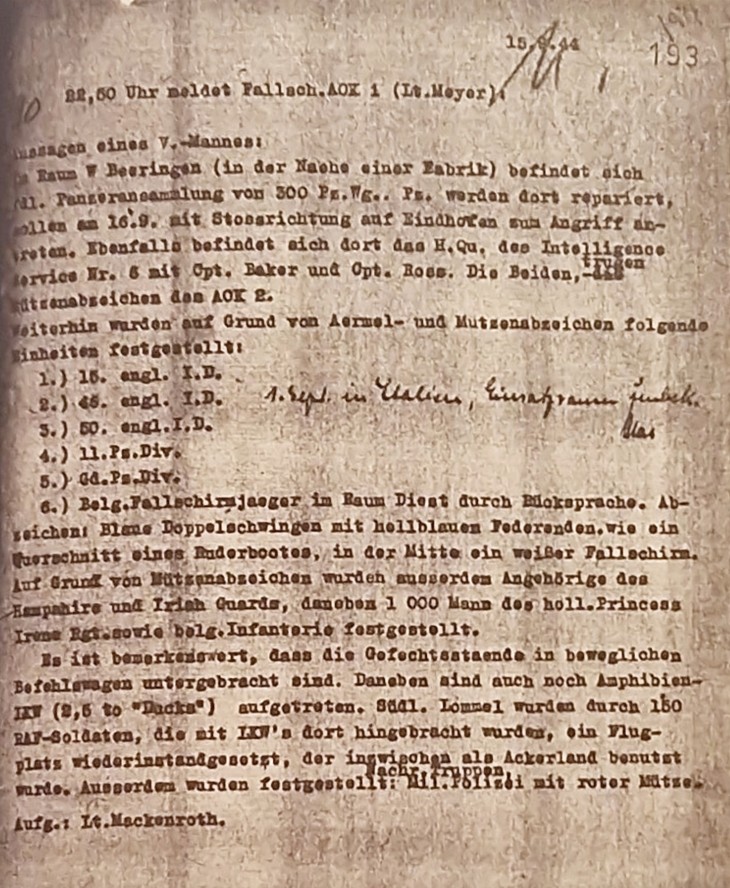

Fig.: Report in German:

9/15/44

At 10.50 p.m.

Fallsch.AOK 1 (Lt. Meyer)

reported:

Statements from an

undercover agent:

Located in

area W Beeringen (near a

factory).

Enemy tank

gathering of 300 armored

vehicles. Tnks are repaired

there, should start attack

thrusting towards Eindhofen

September 16th. The H.Q. of

Intelligence Services No. 6 with

Cpt. Baker and Cpt Ross is also

located there. Both wore cap

badge of the 2nd Army.

Furthermore, based on sleeve and

cap badges, the following units

were identified:

1) 15th

English I.D.

2) 45th English

I.D.

[handwritten:

“September 1st in Italy,

operational area unknown

(illegible)]

3) 50th English

I.D.

4) 11th Arm. Div.

5)

Grenadier Arm. Div.

6)

Belgian paratroopers in the

Diest area by consultation.

Insignia: Blue double wings with

light blue feather ends, like a

cross section of a rowing boat

with a white parachute in the

middle.

Based on cap badges,

members of the Hampshire and

Irish Guards, alongside 1,000

men of the Royal Princess Irene

Regt. and Belgian Infantry

identified.

It is noteworthy

that the command posts are

accommodated in mobile command

vehicles.

In addition, there

also amphibian trucks (2.5 to

“Ducks”) are deployed. South of

Lommel an airfield, that in the

meantime was used for farmland,

is repaired by 150 RAF soldiers

who were brought there in

trucks, an aircraft.

Also

noted were: Signals Troops, Mil.

Police with red cap.

Signed:

Lt. Mackenroth

|

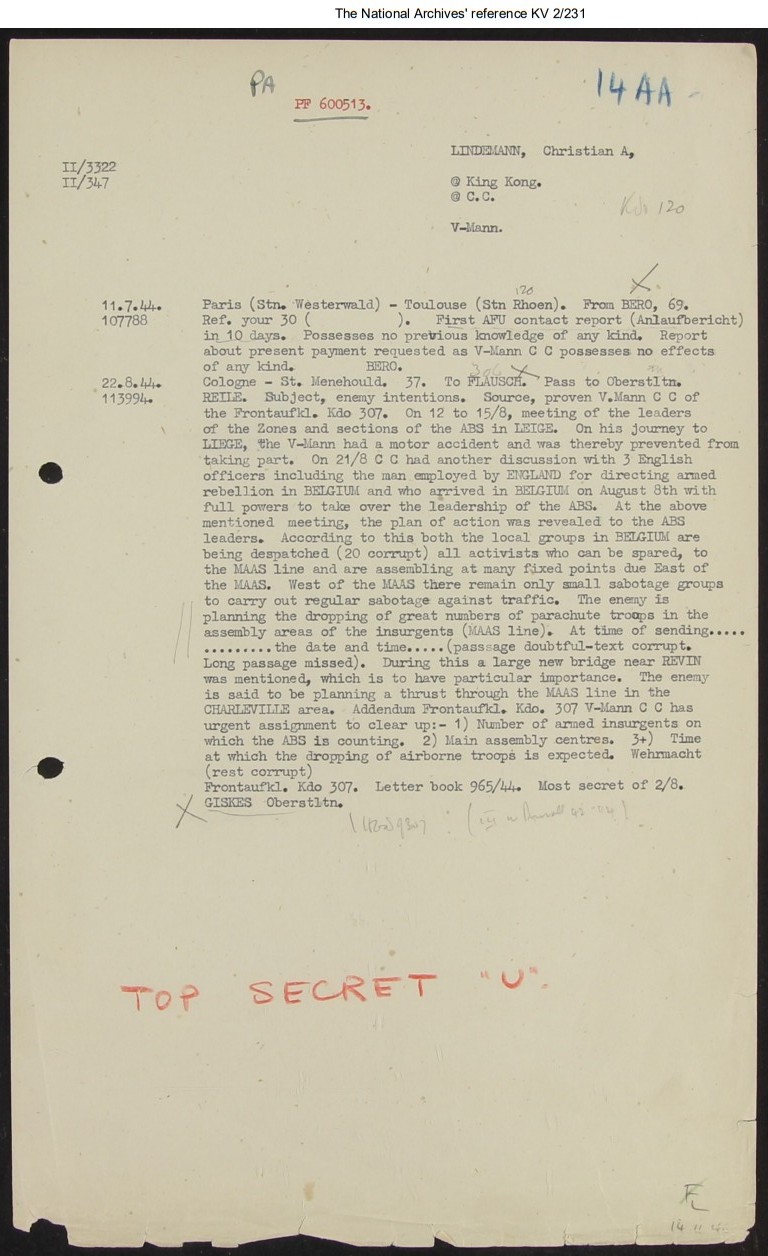

4) In File KV-2-231 in

British National Archives:

Transcript of German

Intelligence message intercepted

by Bletchley Park dated

22AUG1944 of King Kong already

relaying intended Airborne

Assault towards Maas. |

(click to enlarge)

Fig.: Intercepted and

decyphered message of 22AUG1944

|

|

5) In

situ: Photo building in

Driebergen. |

(click to enlarge)

.JPG)

Fig.: Villa Heijdesteijn in

Driebergen where the German

Frontabwehrtrupp 365 (Front

Intelligence Troop) was

stationed and where Lindemans

provided the Germans with

intelligence described in the

15SEP1944 report.

The estate

is NOT open to

the public. |

On 17SEP1944 a Horsa glider with

chalk number 413 was forced to

make an emergency landing near

Dongen because of a broken tow

cable. The glider was part of

“A” Squadron, No. 8 Group,

transporting General Frederick

Browning’s headquarters. On

landing the crew was attacked by

a group of German soldiers and

one crew member was killed.

After interrogation and having

searched the plane, the Germans

found a document, probably the

day order of the 101st airborne

Division. It was handed over to

Generaloberst Student who in

turn was unable to contact

Feldmarschal Model. It was

therefor impossible to pass on

the information in this document

to German commanders in the

Arnhem area of operations. But

Student himself was now aware of

the route of advance of XXXth

corps, the drop- and landing

zones and the objectives of the

101st. The document also

included the transport schedule

of 18 and 19SEP1944. Using this

information, Kurt Student was

able to reorganize his forces.

|

Factor Most Dangerous

Course of Action

Germany’s strategic reaction

facilitated the flexible use of

military assets. 15th Army units

were pulled away from the

Scheldt Estuary and provided the

bulk of the infantry used to

challenge Operation “Market

Garden”. Heavy tank battalions

were rushed to the area by

train. It was Germany’s ability

to prioritize these trains, even

in late 1944, that meant British

and American paratroops with

only light anti-tank

capabilities, had to deal with

Panther tanks and Tiger II’s.

|

|

CONCLUSION:

Operation "Market Garden"

failed because the ground forces

did not reach all the areas

captured by airborne forces.

It is the opinion of this

agency that the battle was as

much influenced by factors of

German fighting abilities as it

was by Allied tactical errors.

Moreover the plan for Operation

"Market Garden" had too many

"moving parts" in which the

failure one task led to a chain

reaction of failure. |

|

EXHIBITS:

This agency is a regular

explorer to the Area of

Operations of "Market Garden"

and has repeatedly visited

numerous locations that are

indicative of the complicating

factors that led to the failure. |

|

(click to enlarge)

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg) _small.jpg) _small.jpg) _small.jpg)

Fig.: From top to bottom:

- Delay of 30th Corps at

Valkenswaard: Metal detecting at

the German ambush site in 2013.

- Drop zones of 1st British

Airborne Divison far from

objective:

Round canopy jump

on Ginkel Heath in 2022.

-

Delay at destroyed bridge at

Son:

Royal Netherlands Army

constructed a Bailey bridge at

this location in 2014.

-

Delay until Nijmegen Bridge is

captured:

Reenacting the Waal

River Crossing in 2024.

- The

Bridge Too Far:

John Frost

Brige in 2014 |

|

Back to Battle Studies

|

| |